Theory and Design

Lately The Algorithm has correctly identified me as an utter nerd, and I’ve been inundated with endless posts and short-form videos about music production. A lot of them can be separated into two categories: music theory and sound design.

The music theory videos are usually more DIY and intellectual. Imagine a GoPro video taken by someone sitting at a piano. They walk you through a cool chord progression while briskly explaining the emotional tension it creates. Frequently they use minor 7ths and dominant 9ths in some sort of inversion. (7ths and 9ths have more notes than a vanilla chord and are often used in jazz.)

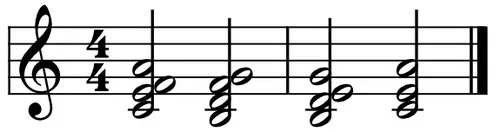

Recently I came across one about The Royal Road. The Royal Road is 4-chord progression that dominates Japanese pop. It’s very chill – fun without being too fun. Importantly, it’s not as simple as the 3-note chord progressions that proliferate in western pop.

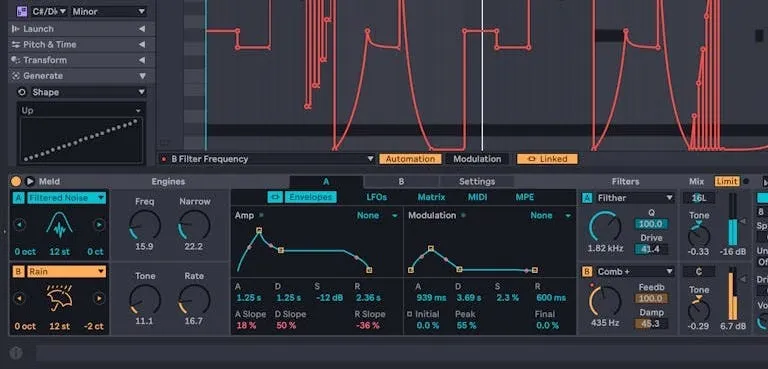

The second category of video, sound design, usually takes the form of a screen cast. A narrator will walk you through the process of crafting a sound using some neat tool they’ve found. Plug your voice into a sampler, chop it up, and play it back like a keyboard. Add a saturator and resonant filter to emphasize different frequencies and adjust the character “to taste.”

Sound design is full of proper nouns and lingo, but if I were to attempt to define it formally, I’d say it is the process of determining the frequencies present in a sound over time.

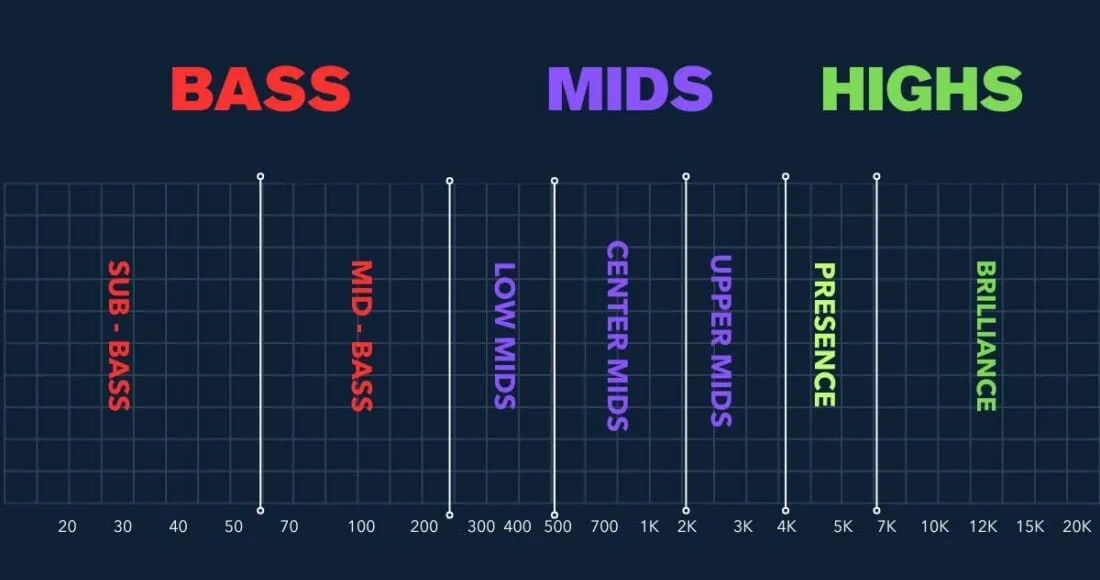

This can be visually represented with a frequency spectrum.

Starting from the left, we graph the bass frequencies in a sound all the way up to the treble and then to the “brilliance” or “air”. (“Air” refers to crackling frequencies far outside the human vocal range that are often occupied by hihat cymbals.)

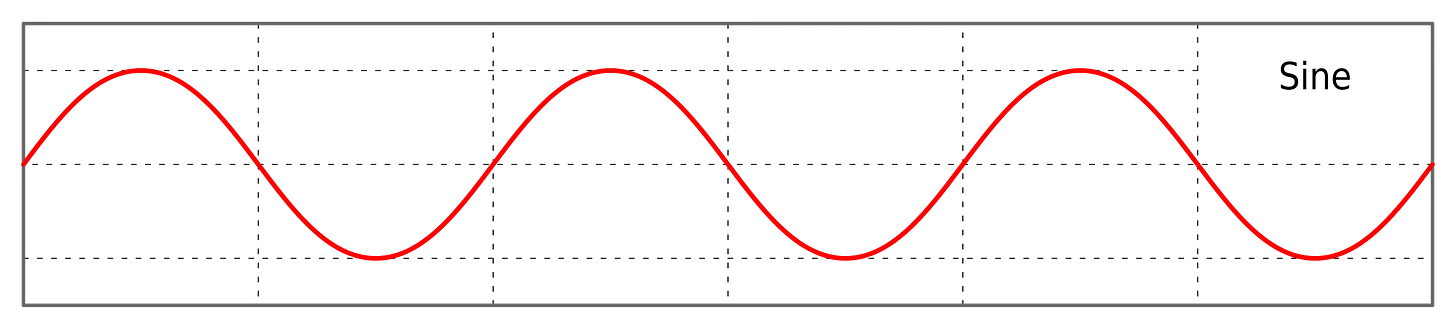

We’ll start with the simplest sound, a sine wave.

Try playing a sine wave on the keyboard below and viewing the frequencies. (Make sure your device’s volume isn’t too loud.)

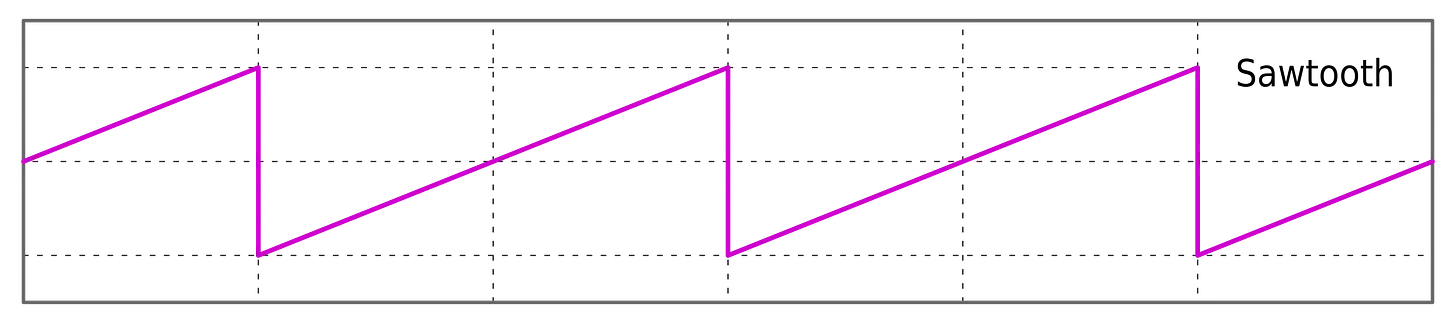

You should see thin spikes at the frequency corresponding to the note you play. We call this the “fundamental frequency”. (Not very interesting, I know.) Now try playing sawtooth wave.

You should now see lots of spikes. We call these successive spikes “harmonics”. Overall a sawtooth wave has much more harmonic information than a sine wave. We might call a sawtooth wave “fat” or “punchy”, while a sine wave might be considered “soft” or “delicate”. This is the core of sound design. We craft sounds to contain different harmonic information and convey a feeling.

Now let’s go back to music theory. What is the frequency spectrum of a chord? Let’s make a major triad with sine waves. Try playing a note on this next keyboard. It will automatically play the other two notes in the chord.

Turns out that the notes in a chord act very similarly to the harmonics in a sound. Next let’s try some 7th chords.

And some 9ths.

We could keep going with this, but you probably get the picture. The more notes we add to a chord, the closer we get to sound design. That is to say, theoretical complexity is equivalent to sonic complexity.

Let’s try that last chord with a sawtooth.

We’ve multiplied the complexity. If you hold down a note, you might even notice some of the harmonics oscillating. This is caused by interference patterns in the interacting waves, part of what we call “dissonance”. We’ve combined a music theory concept, a chord, with a sound design concept, a sawtooth wave, to create a note with its own movement.

I like to frame western music in three historical phases: classical, jazz, and pop. For a few centuries classical was considered the pinnacle of music. Composers had a fixed set of instruments and used theory to conjure rational melodic complexity. In the early 1900s, jazz musicians used many of the same instruments to toy with irrational melodic complexity. Free jazz in particular evoked something akin to noise. Not long after, guitarists discovered that they could create new harmonics by overdriving their amps. A power chord contains only two distinct notes, but distorted through an amp it has a lot of sonic complexity. Pop music today often leans on simple chords, but it achieves much of its complexity through sound design.

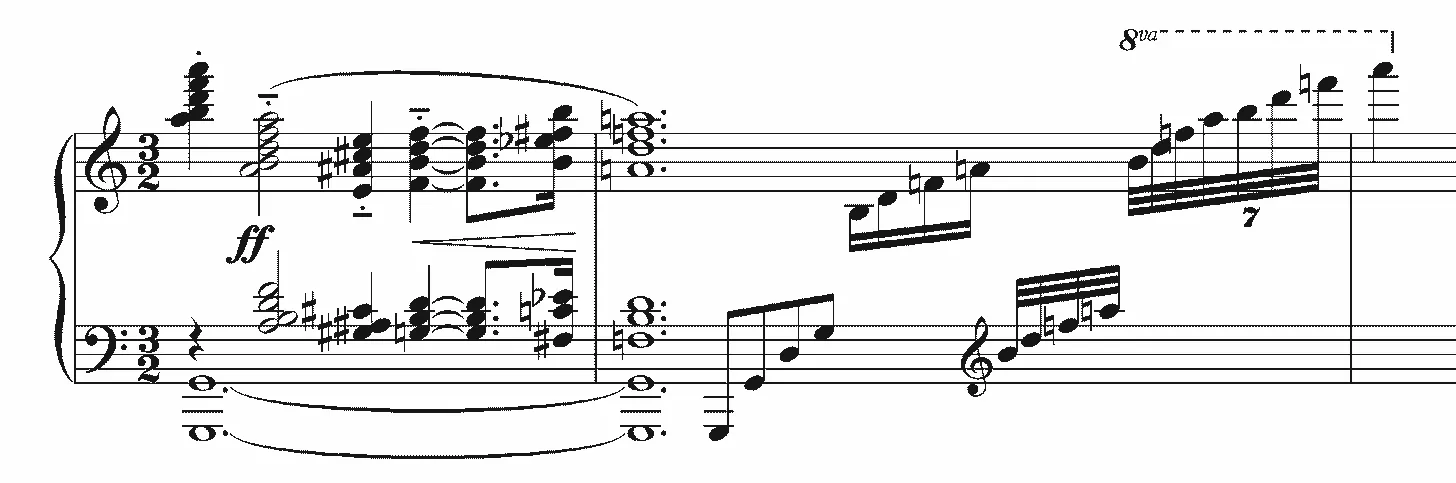

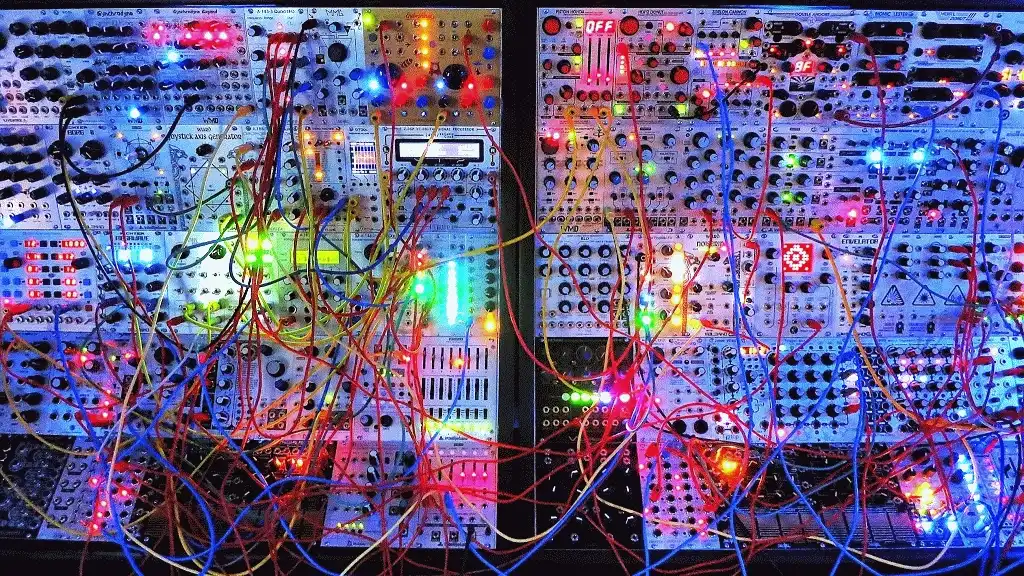

So when I see a Debussy piece with chords like this.

It doesn’t appear too different than a synthesizer patch like this.

Both are attempting to generate the right frequencies at the right times.